Tel River Civilization [English]

I spent my childhood in Tusura, a small town of about 10,000 people near Balangir, Odisha. On the way from Tusura to my ancestral village, Dangarmunda, the Tel River lies along the route. Dhanghara, a part of the Tusura Notified Area Council, is on the bank of the Tel River. I lived 1.5-2 km away from it. I remember being fond of looking at the Tel River as a kid when we used to go to our village. During my school days, my friends and I went to the Tel River bridge on my Hercules bicycle many times just for fun. Sonepur, the city where my mother is from, is also on the bank of the Tel River (along with the Mahanadi). So my ancestors on both sides have lived near it.

One day I was randomly checking the Wikipedia page for Balangir; one thing led to another, and I found an interesting paper on the Tel River civilization. It was fascinating. I thought I should write a blog about it. I am also writing an Odia version of this blog, will update it soon.

The Tel River originates in the Nabarangpur district of Odisha, near the Odisha-Chhattisgarh border. It flows through the Nabarangpur, Kalahandi, Nuapada, and Balangir districts and finally merges with the Mahanadi at Sonepur. It carries the stories of people, civilizations, migrations, trade, and culture. The blog is divided into three parts: the prehistoric ages, which cover the Stone Age, Copper Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age; text-based accounts from the early historic period (5th-3rd century BCE); and finally Asurgarh Fort. I will start with the Stone Age.

Prehistoric ages

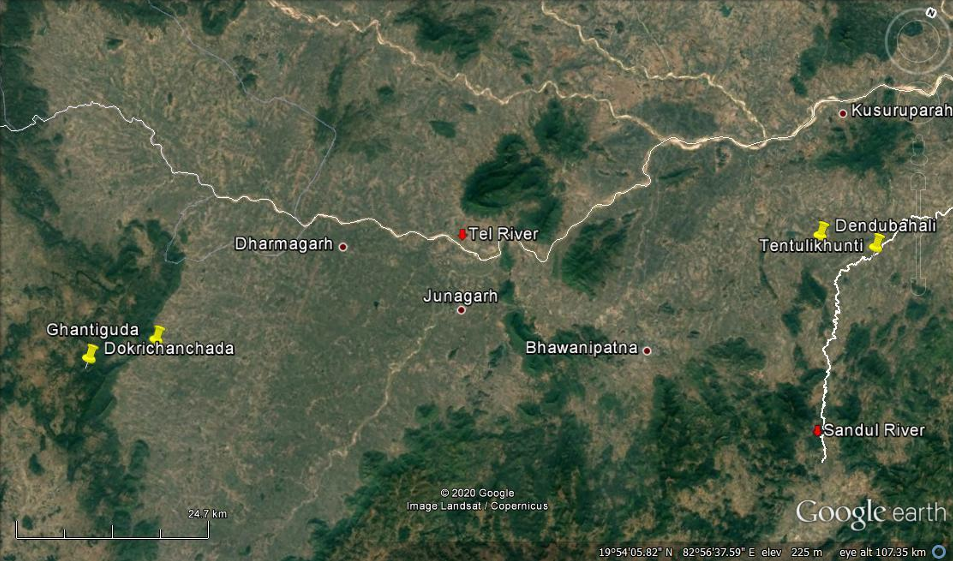

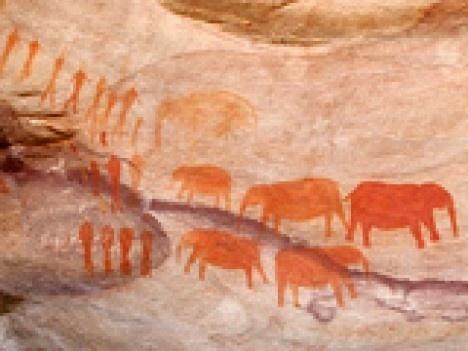

I was kind of surprised when I got to know that much evidence of Mesolithic (end of hunter-gatherer era) and Neolithic (end of Stone Age) settlements have been found in Kalahandi. It is incredible to think that people once walked this land using stone tools like axes and chisels while also crafting microliths(small stone tools). Archaeologists found tools like mullers (grinding stones), pestles, cup marks (small circular carvings on rocks), and stone ploughshares (early plough parts). These are processing tools, which hint they were processing grains, tilling soil, and preparing food. Also, paintings in Yogimath (in present-day Nuapada district) depict scenes of early village life. I have attached an image of Google Earth views of four Palaeolithic sites of Tel river valley and image of Handaxe from different Palaeolithic sites of Tel river valley(credit: Dr Nalinikanta Rana). I have also attached an image of Yogimath paintings(credit: Odishadairy).

When people started living together in settled communities instead of moving around as hunters and gatherers, and that led to shared rituals and customs to stay united as a community. Many current traditions, taboos, and beliefs in that region still carry traces of ancient agricultural practices.

The valley then saw a gradual change. People moved on from stone to copper. Archaeologists have found objects made of copper like rings, bangles, and griddles (flat metal plates used for cooking). It is itself a major technological leap. Along with those copper tools, microliths were also found. This shows coexistence of stone and metal tools indicating transitioning from Stone Age to Metal Age.

It gets interesting at Jamgudapar, where they found bronze objects, (first of its kind in Odisha btw). Bronze, being an alloy of copper and tin representing metallurgical advancement, makes it very significant.

Pottery pieces and their fragments of different kinds and colors (black-red, red, black-slipped) have been found in Kalahandi and Balangir districts. They were decorated with carved lines, triangles, and paintings. The pottery fragments were made on the potter’s wheel, using refined clay and often had a smooth shiny coating-showing aesthetic expression and good craftsmanship.

Moving on towards Iron Age, tools like spearhead, arrowhead, sickle, and hoe, nail, pin, bangle, bowl, and ring, etc., iron slag, semiprecious stone beads, brick tiles, graffiti traced on exterior and interior of the broken ceramic materials, recovered from proto and early historical settlements in Kalahandi district suggest influence or interaction between the southern Megalithic (massive monuments) culture and the valley-perhaps through migration, trade, or shared traditions. The Iron tools were used to clear jungles and the lands were used for cultivation.

These agricultural, artistic, metallurgical etc advancements resulted in a mixed society.

Text based accounts

We should talk about historical accounts now. Panini’s Ashtadhyayi references the Telavaha River and its Janapada Tailaka, which researchers link to current Tel River and Titlagarh region. He mentions these names in a commercial context, referring to Titila-Kardu, meaning rhinoceros hide. Archaeological findings, including rhinoceros pendants and coins with rhino symbols, confirm that they once lived in the valley and had cultural and economic importance.

In the Buddhist Seravanjita Jataka, two towns-Andhapura and Teringri-are mentioned along the Tel River. Many scholars believe today’s Kharligarh was once Adhapura, the center of Andhra tribe. Archaeology backs this up: forts, pottery, and signs of trade found at Kharligarh and Terasingha show that between 500 and 200 BCE, the Andhras lived settled lives here, shaping early towns and trade networks.

Jain text Jambudivapannatti adds another layer to the tale. It speaks of a city called Kanchanapura (the city of Gold) in Kalinga which resonates with Suvarnapura (modern-day Sonepur). Historians think that during medieval times this place may have been known as Pashimalanka (Lanka of the west), hinting that people from southern India may have migrated and settled along the Tel.

By the Gupta period, the region was known as Atavika or Mahakantara, ruled by King Vyaghraraja. His kingdom appears in the 4th-century Prayagraj pillar inscription and in Varahamihira’s writings. Some believe Asurgarh at Kesinga could have been its capital. Even earlier, the Mahabharata mentions Kantara, where Sahadeva is said to have defeated the ruler of South Kosala.

Though no large-scale horizontal excavations have been done in the valley as of now, artifacts, inscriptions, and texts tell a story. Towns grew along the riverbanks, the Tel and its tributaries served as inland trade routes, and luxury goods moved across regions. All this points to thriving urban centers with strong industrial and commercial life.

Asurgarh and Mahakantara State

Asurgarh fort (in modern-day Kalahandi district) is an important place to know about the valley’s history during 3rd-5th Century CE. The details of the fort are interesting.

It was protected by a massive wall of brick and rubble, still measuring about 21x14 inches in height and width, with four gateways opening in all directions. A wide moat, about 15-18 meters across, surrounded the fort. Beyond it lay the lower town-the residential area-spreading over nearly 8 km in circumference and enclosed by an outer mud wall. Watchtowers stood at four cardinal points (four directions) within this boundary. I used Google’s Nano Banana Pro to generate an image of how the fort would have looked like.

To the east of the fort, there is a huge water reservoir covering around 200 acres, while a smaller tank once existed to the south. The river Sandul flowed close to the western moat and was cleverly diverted by an anicut to channel water into the fort, creating a well-planned system to keep the moat filled.

A small excavation in Asurgarh in 1973 revealed a rich past. Mauryan-polished sandstone, punch-marked coins from pre-Mauryans to post-Mauryan times, remains of a brick temple, terracotta figures, bangles, beads, iron tools, Kushana pottery and coins, NBP ware, and even a Vishnu icon from the 5th century AD. Evidence of coin moulds and bead-making units shows local industry, placing Asurgarh’s cultural life between the 3rd century BCE and 5th century.

A copper plate discovered at Teresinga (a village 2 km away from Asurgarh) records King Tustikara granting land to a Brahmin devotee of Goddess Stambeswari, hinting at rising local chiefs and strong ties with wider trade and cultural networks. The scale of the fort, its water system, and the presence of a mint suggest Asurgarh was the heart of the Mahakantara state. Around it, places like Budhigarh and Kharligarh formed pastoral zones, while Koraput and Bastar made up the forested regions, ruled by semi-autonomous chiefs. Although this balance collapsed after Samudragupta’s Deccan campaign, which weakened King Vyaghraraja and led to the breakup of Mahakantara by the early 5th century AD.

Most people living here are not aware of all these historical facts. This blog is an attempt to bring it to public disclosure. Also huge thanks to Dr. Baba Mishra and his paper “EARLY HISTORY OF THE TEL RIVER VALLEY(2003)”, and Dr. Nalinikanta Rana and his paper “Palaeolithic Culture of the Tel River Valley, Kalahandi(2020)“.

References:

[1]: EARLY HISTORY OF THE TEL RIVER VALLEY, Baba Mishra(2003)

[2]: Palaeolithic Culture of the Tel River Valley, Kalahandi, Dr Nalinikanta Rana(2020)

If I made any mistakes here, please let me know. I hope you liked this post. If you want to say Hi or anything, here’s my Telegram @ashirbadtele or you can mail me at ashirbadreal@proton.me.